How the Art Auction Process Actually Works

International Volunteer Day © Keith Haring 1988

International Volunteer Day © Keith Haring 1988Market Reports

The art auction market operates within a structured yet dynamic framework, where strategy, valuation, and market trends converge to determine the success of a sale. While high-profile auctions often capture headlines with record-breaking results, the mechanisms that drive these sales remain opaque. For sellers, navigating consignment terms, reserve prices, and auction fees is crucial to maximising returns. For buyers, understanding bidding strategies, provenance considerations, and post-sale obligations can make the difference between a well-informed acquisition and an overvalued purchase.

Glossary of Key Terms

Reserve Price: The minimum price that a seller would be willing to accept from a buyer.

Buy-in Fee: A charge the seller pays to the auction house even if their artwork doesn't find a buyer, covering the costs of listing and marketing the piece.

LDL: Stands for Loss, Damage, Liability, and refers to an insurance fee.

Provenance: The history of ownership of a work of art.

Selling At Auction

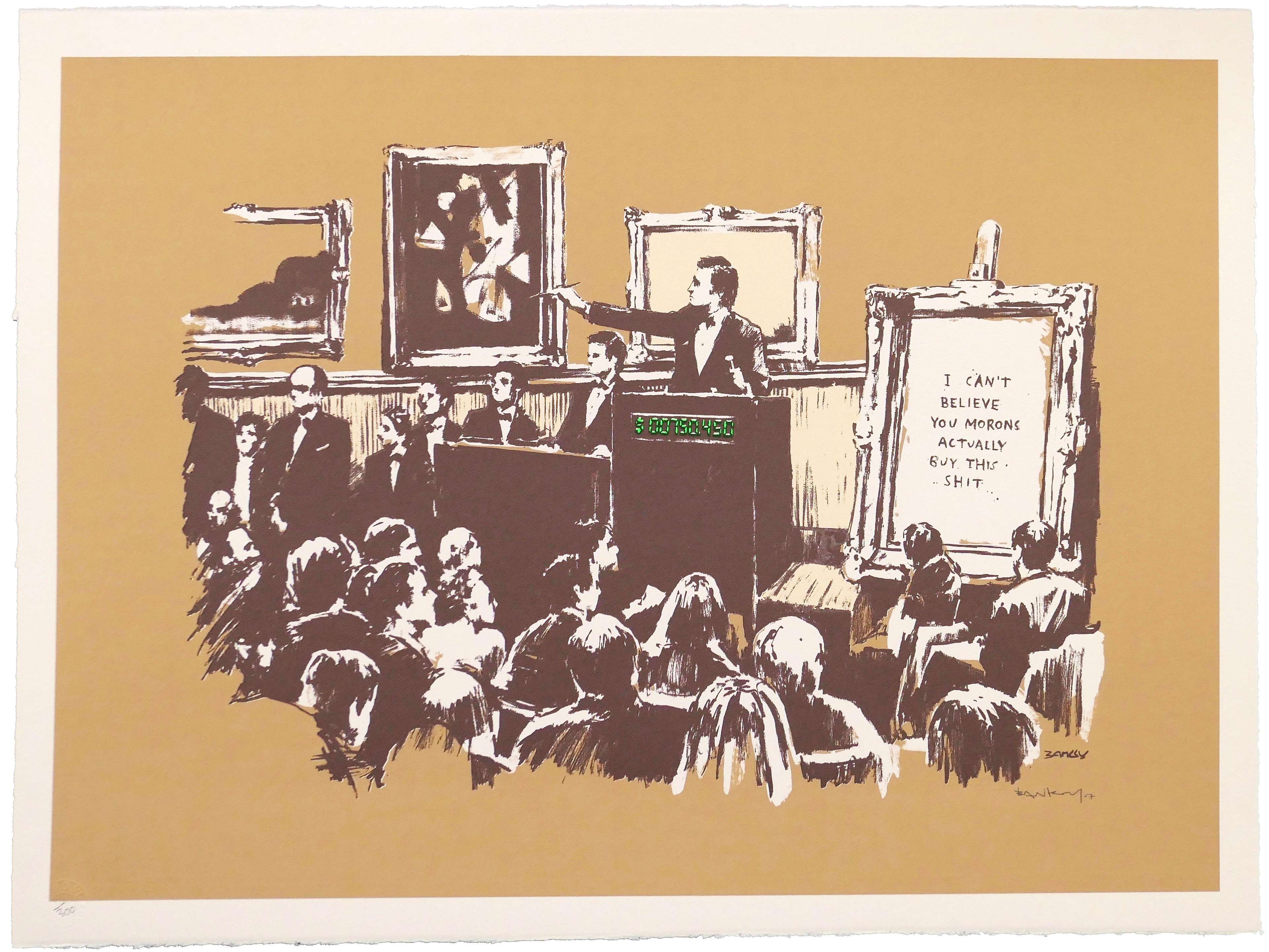

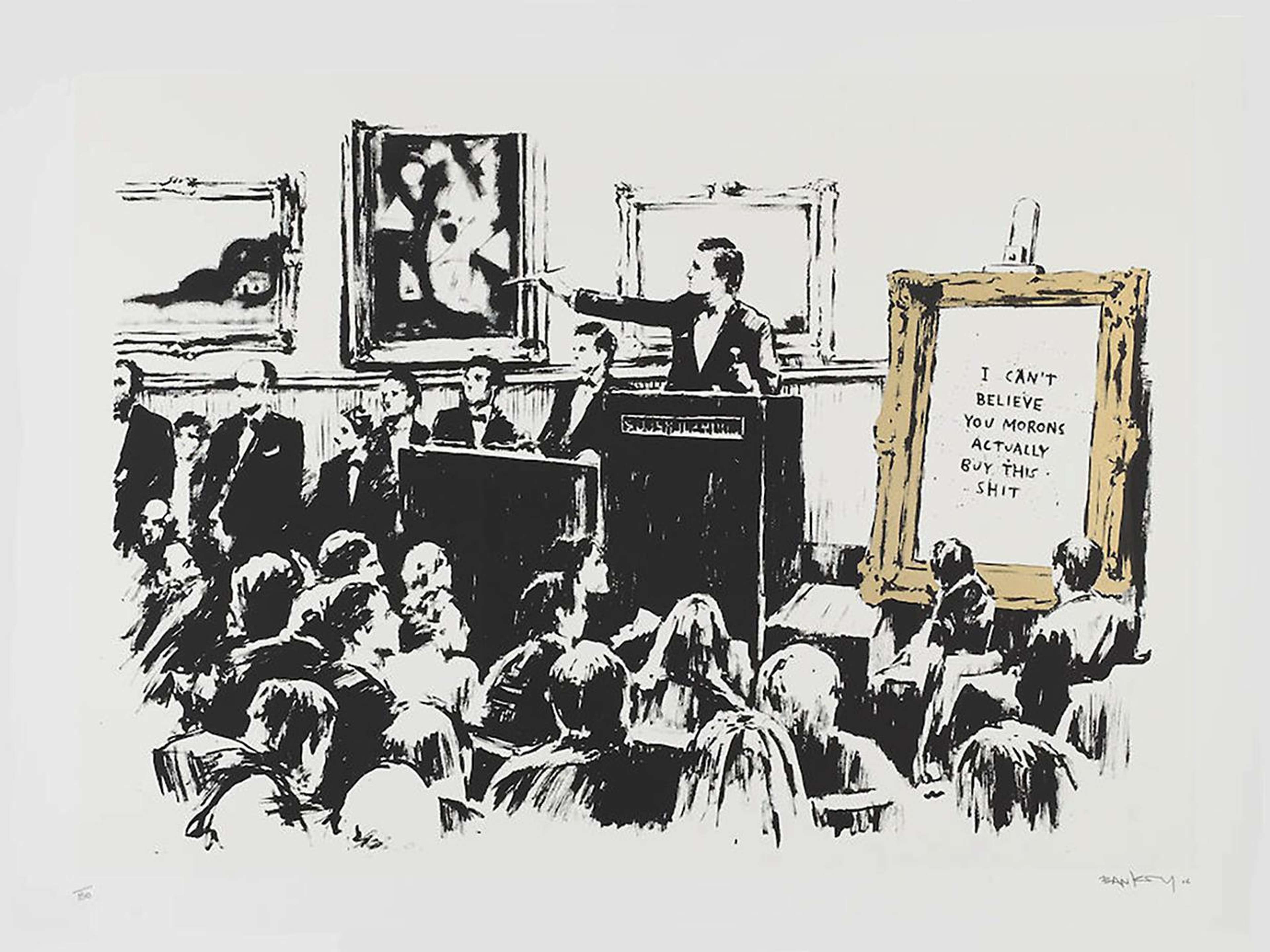

Sellers do not need to handle condition valuations themselves - auction houses typically manage this process. After receiving high-resolution images, the house will suggest an estimated price. Once the artwork arrives in-house, the estimate may change based on condition evaluations. Unlike other markets, auction houses rarely suggest restoration before selling prints. However, certain markets, such as Banksy’s, may be exceptions. Restoration is more common in private brokerage sales, where sellers invest in repairs to maximise value before listing.

The Consignment Process

At the heart of any auction house is the consignment process, where individuals or collectors send their art to be sold in an auction. The steps involved may differ based on the artwork's value, but for most consignments, the process begins by submitting the artwork for valuation, typically through an online form or via email to the auction house's administrator. Sellers don't usually speak to the specialists at this early stage unless the artwork is highly valuable. The administrator provides an initial estimate for the artwork, which may evolve as the consignment date approaches.

The consignment deadline for an auction is generally around a month before the sale. If the seller submits their artwork close to the deadline and the auction house is working towards that consignment deadline quite heavily, the seller will likely receive feedback quickly. However, if the deadline is missed, the artwork might not appear in an auction for a few months, depending on the auction house’s schedule. At this point, the seller is typically informed that their artwork may be included in a future sale but will need to wait.

While waiting for a sale, the seller must accept that they have limited control over how many similar pieces will be consigned at the same time. For example, if multiple editions of the same print are sold in an auction, this can diminish the rarity and desirability of each individual print, impacting its final price. This supply-and-demand principle is critical to understanding the dynamics of art auctions.

Once consigned, the auction house will provide the seller with an auction estimate and agree upon a reserve price. If the bidding does not reach this reserve, the artwork will remain unsold. The auction house will also charge a standard seller’s fee of around 15%, which is deducted from the final hammer price. If the artwork remains unsold, there are additional fees, known as “buy-in fees”, which are often negotiable.

Researching the Market

For both buyers and sellers, researching the market before entering the auction process is crucial. Buyers must be cautious of relying solely on platforms like Artsy, where artworks are sometimes overpriced and can sit unsold for extended periods. These platforms, while offering some visibility, lack the specialised knowledge and valuation standards that traditional auction houses and MyArtBroker provide.

It is important to understand that auction results do not always reflect the actual amount the seller will receive. For instance, if an artwork sells for £125,000 at auction, the seller will likely only see a portion of that figure after the auction house takes their 15% commission and any additional fees.

The Role of Provenance in Valuation

When determining the value of an artwork, provenance is a critical factor. Provenance can significantly impact the price, especially if the piece comes from a prestigious collection. For example, prints from celebrity-owned collections achieve higher prices because buyers value not just the artwork but its historical association. This was most recently seen in Christie’s 2024 auction; The Collection of Sir Elton John: Opening Night. However, provenance isn't always a guarantee of quality. The fact that an artwork has been sold at a prestigious auction house like Christie’s does not automatically make it authentic or valuable. Auction houses typically guarantee authenticity for only five years, meaning scholarly opinions can change.

Another potential red flag in provenance is a problematic gallery in the artwork’s history. If a piece has passed through a gallery known for selling forgeries, it may raise doubts - even if the artwork is legitimate. Buyers should research provenance beyond the last sale to ensure no black marks on the artwork’s history.

Provenance can be documented in different ways, including invoices, receipts, letters, or even photographs proving a connection to the artist. While a certificate of authenticity may seem reassuring, buyers should also obtain comprehensive documentation and expert verification.

Additional Costs

In addition to the seller's fee, there are several other charges that sellers must be aware of. These may include:

- Marketing fees: Auction houses often charge marketing fees, depending on how prominently the artwork is featured in the auction catalog. The scale of the marketing may affect the artwork’s visibility to potential buyers.

- LDL insurance: This is an additional fee for insuring the artwork during its time at the auction house.

- Performance fees: If the artwork sells for above its high estimate, a performance fee of 1-2% is charged on top of the standard seller's fee. This incentivises auction houses to set realistic estimates to maximise the sale price, which in turn benefits both the seller and the auction house.

- Cataloguing fees: Some auction houses also charge a cataloguing fee for including the artwork in the sale catalogue.

What Happens When an Artwork Doesn’t Sell?

If a piece does not sell at auction, it can be marked as “burnt” or “BI” (bought in), which can have a lasting impact on its resale prospects. This term refers to artworks that were offered for sale but failed to attract a buyer at their reserve price. For prints, the specific edition number is often marketed alongside the work. If that piece doesn’t sell, the unsold artwork is considered “burnt” - damaged goods, in other words - and it may take up to a year before it can be offered again in a future sale.

Auction houses will often advise sellers against setting their reserve price too high, as this can increase the likelihood of the artwork remaining unsold. A failed sale doesn’t just affect the seller but also impacts the auction house's reputation. Auction houses are motivated to maintain a high sell-through rate, which means ensuring as many lots as possible sell during the auction.

Buying At Auction

The Bidding Process

Before participating in an auction, buyers must undergo Know Your Client (KYC) checks. Once approved, bidders can participate in multiple ways:

- Absentee Bids: A bidder submits a maximum price in advance, and the auction house bids on their behalf.

- Telephone Bidding: A representative calls the bidder during the auction to relay real-time bids.

- Live Bidding: Bidders participate in real-time, either in person or online.

A condition report is essential before bidding. Buyers should never bid on a print without a detailed condition report, which should list specific issues (e.g., foxing, fading, burn marks) rather than vague descriptions like “good” or “fair.”

Auction houses employ bidding strategies to encourage higher prices. Seasoned bidders often wait until the last possible moment to bid, preventing unnecessary price inflation. Newcomers should be wary of overbidding - by definition, the winning bidder always overpays by at least one increment, since the fair market value is set by the previous highest bid.

Introducing Priority Bidding

In response to shifting buyer behaviours and a desire to inject momentum into early bidding, Phillips has introduced a first-of-its-kind Buyer’s Premium Structure featuring Priority Bidding. This process rewards collectors who place written bids at least 48 hours in advance of a live auction with significantly reduced premium rates. For example, successful Priority Bidders in New York benefit from a 25% rate on the first $1 million of the hammer price, compared to the standard 29%. Reduced rates also apply to higher tiers and mirror those in London, Hong Kong, and Paris sales.

Unlike traditional absentee bids, Priority Bids must meet or exceed the lot’s published low estimate and are binding - yet the reduced premiums apply whether the winning bid is the Priority Bid or a higher one placed by the same buyer during the auction. By encouraging early engagement, Phillips is offering greater value to proactive bidders and creating more competitive momentum in the opening stages of its sales.

What Happens After Winning a Lot?

Winning an auction comes with immediate responsibilities. If the bid was placed absentee, the buyer will receive a notification of success, followed by an invoice from the auction house.

The payment process varies by auction house, but typically:

- Buyers must transfer funds before the artwork is released.

- The piece is stored for two weeks free of charge.

- Shipping arrangements depend on the artwork’s value - high-value pieces may be shipped by the auction house, while lower-value purchases require self-arranged shipping.

Buyers should be mindful of storage fees, which accrue daily after the two-week window. In some cases, storage costs can exceed the price paid for the artwork - especially for large interior pieces like furniture. If a buyer refuses to collect their purchase, auction houses may resell the artwork, but they will deduct a 15% seller’s fee from the new sale price.