Pablo Picasso’s Printmaking Techniques

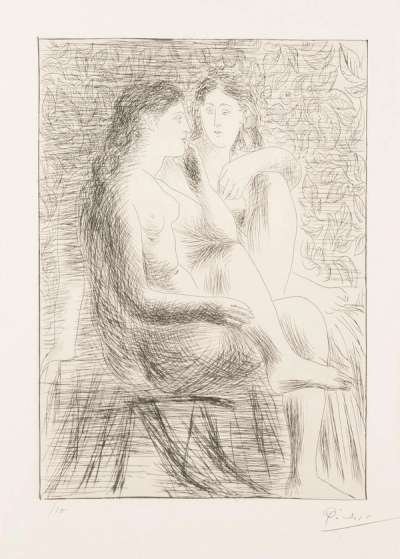

Le Saltimbanque Au Repos © Pablo Picasso 1905

Le Saltimbanque Au Repos © Pablo Picasso 1905

Pablo Picasso

137 works

Key Takeaways

Beyond his iconic paintings, Pablo Picasso ventured deeply into printmaking, mastering techniques such as etching, lithography, and linocut. He approached the medium not merely as a method of reproduction, but as a dynamic space for innovation and bold experimentation. Through his prints, Picasso conveyed profound emotional complexity, demonstrating his relentless pursuit of artistic evolution and his drive to challenge convention.

Pablo Picasso's artistic legacy extends far beyond his renowned paintings and sculptures, encompassing his deeply significant exploration of printmaking. While celebrated for pioneering movements like Cubism, Picasso’s printmaking reveals a quieter, more intimate dimension of his creativity. Through techniques such as etching, engraving, lithography, and linocut, he not only embraced the medium but transformed it, reflecting his relentless innovation and desire to experiment. In this medium, as on canvas, Picasso’s genius was evident in his ability to reimagine forms and techniques, contributing to a body of work as diverse in its execution as it is profound in its impact.

Early Engagement with Etching and Engraving (1900s)

In the early 1900s Picasso ventured into printmaking, focusing initially on etching and engraving; two intaglio techniques that involve incising lines into metal plates. These methods, with their precision and delicacy, allowed for an intimate form of expression that attracted Picasso and became a medium he would revisit throughout his career. His early etchings from this period, particularly during his Blue Period, reveal a synthesis of technical mastery and emotional resonance. In these works Picasso captured a deep sense of melancholy, the restrained use of scale and colour in these early prints subtly foreshadowing the bold experimentation that would later become synonymous with his art. These etchings not only served as a precursor to his future stylistic innovations but also highlighted his early engagement with the deeply personal themes of human suffering, isolation, and uncertainty.

Picasso’s Iconic Series

La Suite Des Saltimbanques

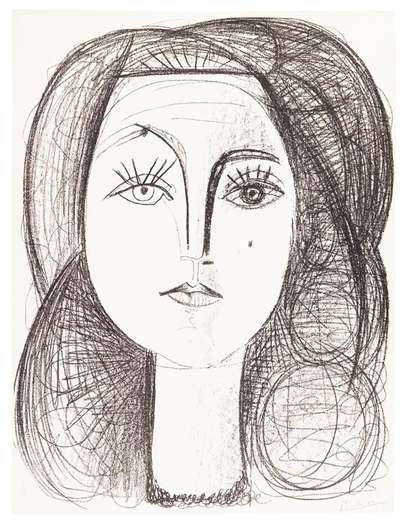

Created between 1904 and 1905, La Suite Des Saltimbanques marks a key moment in Picasso's career. This series of etchings delves into the world of circus performers, a recurring motif in Picasso’s work that mirrors his own feelings of alienation during his early years in Paris. The performers, often acrobats or street performers, occupy a unique space on the fringes of society, embodying themes of displacement and vulnerability; concepts that resonated with Picasso’s personal experience as an artist striving to establish his place in a foreign city. The series features notable works such as Le Repas Frugal and Le Saltimbanque Au Repos, which capture the delicate balance between the physical and psychological states of these itinerant performers. The figures, whether portrayed in intimate group settings or isolated moments, exude a quiet introspection that defines Picasso’s Blue Period. Their melancholic expressions and fragile postures reflect not only the hardships of their transient lifestyles, but also the emotional depth that Picasso was able to convey through the simplicity of line and shadow.

In the context of his broader work, La Suite Des Saltimbanques represents a period of transition and artistic growth for Picasso. The series signals his movement from the sorrowful tones of the Blue Period toward the warmer, more optimistic palette of the Rose Period. It also underscores his evolving exploration of the human figure, not just as a subject of physical representation, but as a vessel for conveying complex emotional narratives. Through these etchings, Picasso elevates the unseen lives of circus performers to subjects of dignity and resilience, capturing their strength in the face of hardship.

La Suite Vollard

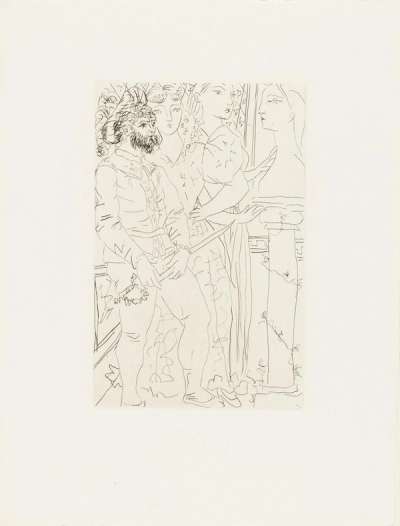

By the 1930s, Picasso’s mastery of printmaking had fully matured, culminating in one of his most iconic series of etchings; La Suite Vollard. Produced between 1930 and 1937, this series of 100 prints is widely regarded as a monumental achievement in the history of modern printmaking. Named after the famed Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who commissioned the works, La Suite Vollard stands as a testament to Picasso’s engagement with both the technical and thematic possibilities of etching. Over the course of the series, Picasso delves into an array of complex themes; love, beauty, classical mythology, artistic creation, and personal relationships, all rendered with a combination of spontaneity and meticulous detail. The prints in this series showcase Picasso’s ability to manipulate line and form with extraordinary fluidity, moving seamlessly from intimate portrayals of sensual love to grand depictions of classical figures such as Minotaurs, fauns, and sculptors.

The series reflects Picasso’s fascination with classical antiquity, yet it also captures his evolving artistic language, particularly as he wrestled with questions about the role of the artist as creator. In many prints, Picasso juxtaposes the mythical and the personal, positioning himself as a modern-day Daedalus or Orpheus, a creator who shapes and destroys with equal fervour. His recurring use of the Minotaur, often depicted as a tortured, blind beast, offers a powerful symbol of the artist’s inner struggles with desire, power, and identity. The technical complexity of the series is equally staggering, with Picasso employing a variety of printmaking techniques, primarily etching, but also aquatint, drypoint, and engraving, to achieve nuanced textures and contrasts. The versatility of these techniques allowed Picasso to push the boundaries of printmaking, creating compositions that range from the highly detailed and ornate, to the starkly minimalist.

Lithography: Picasso’s Bold and Experimental Approach

Collaboration with Fernand Mourlot

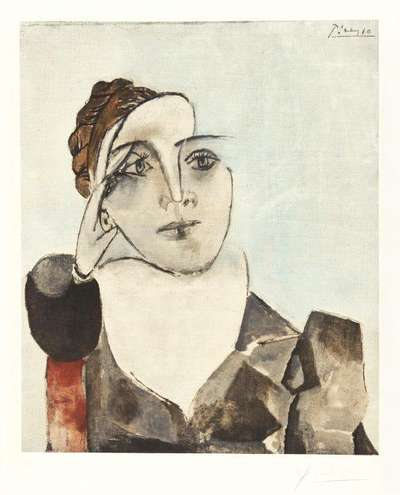

From the 1940s, Picasso's artistic journey took a bold and experimental turn as he embraced lithography as one of his primary printmaking techniques. Lithography, a process that involves drawing or painting directly on a stone or metal plate, offered Picasso a new avenue for creative exploration. It allowed him to experiment with a vast range of forms, textures and colours in ways that felt liberating and unfamiliar compared to his previous work in etching and engraving. Lithography’s immediacy, flexibility, and capacity for layering proved ideal for Picasso, who thrived on pushing the boundaries of any medium he encountered. Over the course of two decades, he produced an astonishing number of lithographs, collaborating closely with master printer Fernand Mourlot in Paris. This collaboration became one of the most significant in Picasso’s printmaking career, marking a period of exceptional innovation and productivity.

Mourlot's expertise in lithographic printing provided Picasso with the technical freedom to explore unconventional methods and tools. For Picasso, lithography was not merely a tool for reproducing images, but an opportunity to transform the act of printmaking into a dynamic, expressive process. He famously used everyday objects, such as kitchen knives and sandpaper, to create textures and marks that imbued his lithographs with an energetic spontaneity rarely seen in printmaking at the time. The freedom of this collaboration allowed Picasso to embrace a more playful and experimental approach, moving fluidly between abstract and figurative styles. His lithographs from this period showcase a range of textures, each print becoming a unique exploration of form and gesture.

Le Taureau Series

One of the most celebrated results of Picasso's lithographic experimentation is his Le Taureau (The Bull) series, produced between 1945 and 1946. This series of 11 lithographs is a remarkable study in the art of reduction, where Picasso progressively simplified the image of a bull, stripping away detail in a step-by-step exploration of form and abstraction. Beginning with a highly detailed and realistic rendering of the animal, Picasso gradually reduced the bull's figure to its most essential elements, culminating in a nearly abstract, geometric version. This process of distillation is a masterclass in Picasso’s ability to capture the essence of a subject while shedding its superficial layers, revealing the inner power and grace of the bull with each successive iteration.

The series also reveals Picasso’s deep engagement with the formal language of Cubism, a movement he co-founded decades earlier, as he deconstructs the bull’s anatomy into geometric shapes and planes. Yet, the reduction does not result in cold abstraction; it emphasises the raw energy and dynamism of the subject. Each lithograph in the series, from the intricate first image to the minimalist final print, exemplifies Picasso’s ability to blend representational and abstract forms through his prints.

Linocut: Picasso’s Revolutionary Approach

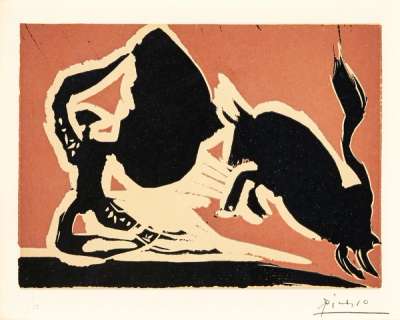

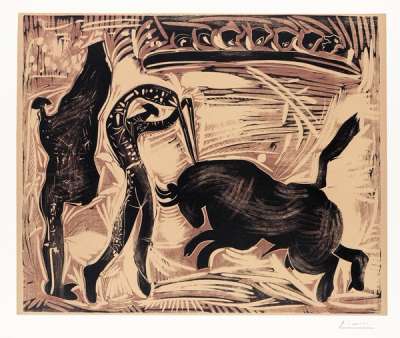

In the 1950s, Picasso turned his attention to the linocut, a technique traditionally associated with simple, bold designs, and in typical Picasso fashion, he saw an opportunity to challenge and expand the possibilities of this medium. Linocut, which involves carving an image into a linoleum block, had long been considered a straightforward technique suitable for producing stark, graphic images. However, Picasso’s radical vision transformed linocut into a sophisticated and complex art form, pushing it far beyond its conventional boundaries.

At the heart of Picasso’s innovation was his pioneering use of the reduction method, an intricate process that involved carving and printing from a single block in multiple stages. With each successive colour, Picasso meticulously removed more of the linoleum, layering one colour over another to build up an image that was both vibrant and texturally rich. This method, which required immense precision and foresight, was particularly demanding because once a portion of the block was carved away, it could not be restored. As a result, Picasso had to envision the entire composition from the outset, planning each stage of colour and form with extraordinary accuracy. This process became a source of creative liberation for Picasso, allowing him to produce prints that were astonishingly complex in both their technical execution and visual impact.

The reduction method enabled Picasso to infuse his linocuts with an unparalleled depth of colour, texture, and energy. His mastery of this approach is perhaps best exemplified in Portrait of a Woman After Cranach the Younger (1958), one of his most famous linocuts. In this work, Picasso pays homage to the German Renaissance master Lucas Cranach the Younger, merging the sharp, clean lines of the linocut technique with a vibrant, contemporary palette. The portrait reflects Picasso’s unique ability to blend the past with the present, honouring classical traditions while simultaneously reinventing them through his modern, avant-garde lens. The result is a strikingly bold image, where the vivid hues and intricate details of the linocut process reveal the possibilities of innovation.

Another prime example of Picasso’s revolutionary approach to linocut is Nature Morte Au Verre Sous La Lampe (1962), a work that highlights his command of form, colour, and light. In this piece, Picasso uses the reduction method to create a harmonious interplay between the geometric shapes of the objects and the luminous glow of the lamp. The work exudes a sense of warmth and vitality, with Picasso’s vibrant colour choices bringing depth and movement to what might otherwise be a static still life. By employing linocut in this sophisticated way, Picasso not only revolutionised the medium but also expanded its potential as a serious artistic form.

Aquatint: Picasso’s Mastery of Tones

Aquatint, a printmaking technique known for its ability to produce subtle tonal variations and gradients, became a pivotal medium in Picasso’s artistic arsenal. Unlike traditional etching, which relies primarily on lines to define form, aquatint is concerned with areas of tone, allowing for the creation of rich, atmospheric effects. For Picasso, who was always seeking new ways to capture the nuances of light, mood, and emotion, aquatint provided a painterly quality that allowed him to experiment with texture and tone in a way that felt akin to his work in other mediums, such as painting and drawing. The ability to build gradients of colour and tone gave Picasso the freedom to imbue his prints with a heightened sense of depth and emotional resonance. His mastery of the technique is evident in the wide range of prints he produced over the course of his career, each demonstrating his ability to manipulate tone to create compelling visual narratives.

Suite 347

Picasso’s mastery of aquatint is evident in Suite 347, one of his most ambitious and celebrated series of prints, completed in 1968. This monumental suite, comprising 347 individual prints, stands as a testament to Picasso’s relentless creativity, and explores a wide range of themes, from the erotic and whimsical, to the mythological and fantastical.

The tonal complexity of Suite 347 is one of its defining features, as Picasso used the aquatint process to evoke a wide array of textures and moods. In some prints, delicate, almost transparent washes of tone suggest a dreamlike quality, while in others, deep blacks create a sense of weight and drama. This ability to shift between lightness and darkness, both in tone and in theme, demonstrates Picasso’s versatility and his command of the aquatint technique. Through Suite 347, Picasso pushed the boundaries of what was possible in printmaking, using aquatint not just as a means of adding tonal variation, but as a central element in his exploration of complex, layered narratives. Whether using the medium to depict moments of quiet intimacy or scenes of heightened drama, Picasso’s mastery of aquatint became yet another example of his ability to transform a traditional technique into a powerful tool for modern expression.

Picasso's printmaking journey stands as a testament to his unceasing creativity and his mastery of diverse artistic techniques. Across etching, lithography, aquatint, and linocut, Picasso displayed a relentless drive to innovate, continually challenging the boundaries of these mediums, and his ability to merge technical precision with profound emotional depth in his prints revealed a more intimate side to the artist. Through his bold experimentation and hybrid approaches, Picasso expanded printmaking's expressive potential, leaving an indelible mark on the medium. His prints, much like his paintings, reflect the complexity of human experience, showcasing his ability to intertwine narrative, emotion, and technical mastery.