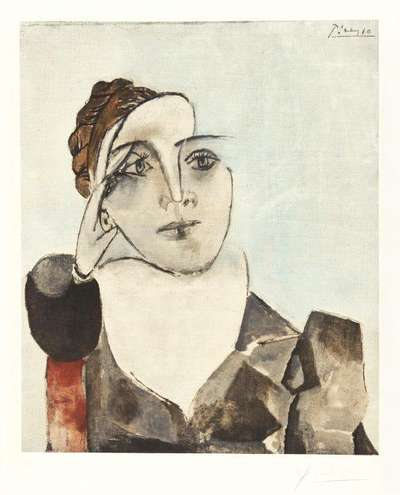

Portrait De Femme II © Pablo Picasso 1955

Portrait De Femme II © Pablo Picasso 1955

Pablo Picasso

137 works

Key Takeaways

Pablo Picasso’s revolutionary art was shaped by a wide array of influences, from European masters like Paul Cézanne and El Greco to African art. His engagement with these diverse sources helped him pioneer Cubism and challenge traditional artistic conventions. However, his interactions with non-Western art highlights the complex dynamics of cultural borrowing under colonialism. Picasso’s legacy is a blend of innovation and appropriation, showing how global artistic traditions and cross-cultural exchanges have both fueled and complicated modern art.

Pablo Picasso's artistic evolution spanned over seven decades, during which he constantly reinvented his approach to art, pioneering styles such as Cubism and contributing profoundly to Surrealism and Expressionism. His works were revolutionary, challenging conventional perceptions of form, colour, and reality itself. However, understanding Picasso’s influences requires more than celebrating his innovations; it also demands a critical examination of the complex dynamics between his work and the cultural sources he drew from. As much as Picasso’s creativity was fueled by an array of inspirations, his engagement with non-Western traditions, particularly African art, often reflected a colonial mindset that resulted in appropriating visual languages without crediting their origins.

Paul Cézanne: The Architect of Modern Art

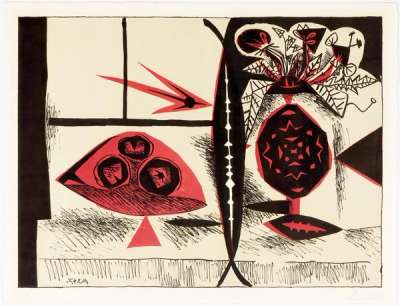

Paul Cézanne’s approach to form, structure, and perspective was perhaps one of the most profound influences on Picasso, particularly during the formative years of Cubism. Cézanne challenged the classical, Renaissance-based techniques of representing reality, breaking away from linear perspective and instead creating dynamic compositions that fractured space into multiple viewpoints. His ability to capture the essence of form without adhering to the confines of realism deeply influenced Picasso. The pivotal moment for Picasso came in 1907, when he attended Cézanne's posthumous retrospective in Paris. This exhibition was a revelation for both Picasso and Georges Braque, who saw in Cézanne’s work a new way of interpreting the physical world. Cézanne’s paintings, particularly his landscapes and still lifes, suggested that reality was not a fixed, coherent structure, but something that could be rearranged, abstracted, and reinterpreted. This concept of breaking down reality into its geometric components directly inspired the foundations of Cubism.

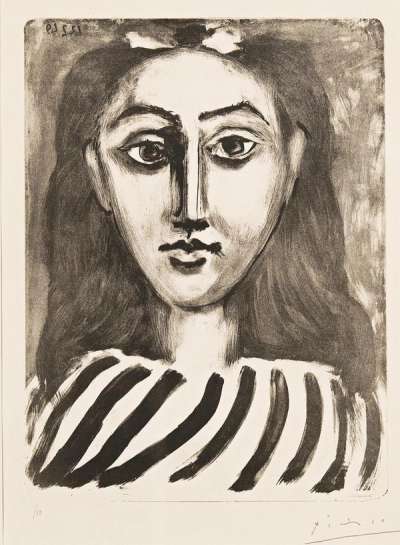

Picasso took Cézanne’s ideas and pushed them further, radically rethinking how the visible world could be represented. In works like Grande Tête De Femme Au Chapeau (1962), Picasso shattered the conventions of traditional perspective, displaying multiple viewpoints on a single canvas. Cézanne had introduced the idea that objects could be seen from different angles within the same composition, but Picasso's vision was even more daring. He completely deconstructed the human figure, turning faces into mask-like forms and dismantling any sense of naturalistic depth or proportion. While Cézanne’s use of flattened planes and fragmented shapes hinted at the subjectivity of perception, Picasso made it explicit. Picasso, building on Cézanne’s groundwork, invited viewers to see the world not as a coherent whole but as a collection of intersecting perspectives, each fragment carrying its own truth. In this sense, Picasso didn’t just adopt Cézanne’s methods, he expanded them into a new visual language that questioned the stability of vision, truth, and identity itself.

El Greco: The Master of Elongated Forms and Dramatic Expression

El Greco’s influence on Picasso, particularly during his Blue Period, cannot be overstated. His dramatic elongation of forms, intense emotionality, and unconventional use of colour attracted the young Picasso. In works like The Old Guitarist (1903), Picasso channels the mystical quality seen in El Greco’s figures, whose stretched, ethereal bodies seem to transcend earthly concerns. This influence is especially evident in Picasso’s melancholic, haunting subjects, who appear trapped in states of sorrow and alienation, reflecting the same existential and emotional depth that El Greco captured in his religious iconography.

However, to limit El Greco’s impact on Picasso to this early period would be reductive. Picasso’s engagement with El Greco’s work evolved and deepened over time, extending far beyond the Blue Period into his experiments with Cubism and abstraction. El Greco’s defiance of conventional artistic rules, his willingness to stretch the boundaries of representation, and his focus on inner emotional landscapes over external realism provided Picasso with a model for artistic innovation. Picasso’s continual reinvention of his style, his refusal to be confined by any one movement or technique, echoes El Greco’s individuality. Picasso absorbed these lessons of distortion and exaggeration, transforming them through his own modernist lens to create an art that, like El Greco’s, transcended the limitations of time, place, and style.

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec: The Bohemian Spirit of Montmartre

During his early years in Paris, Picasso immersed himself in the dynamic, bohemian atmosphere of Montmartre, a hub for avant-garde artists, where he was introduced to the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lautrec's vivid depictions of cabaret dancers, circus performers, and the working-class figures of Paris captivated Picasso, who was equally fascinated by the energy and complexity of urban personalities. Lautrec’s ability to blend caricature with sharp realism offered Picasso a model for capturing the vitality of human expression, something that became central to Picasso’s own explorations of modern life.

The influence of Toulouse-Lautrec’s bold, graphic style is especially evident in Picasso's early works, where he adopted a similar approach to portraying Parisian nightlife. Picasso admired Lautrec’s innovative use of simplified forms and his mastery of line, both of which allowed him to communicate a sense of immediacy and emotion with minimal detail. Though Picasso and Toulouse-Lautrec eventually pursued distinct artistic trajectories; Lautrec remaining more rooted in representation while Picasso moved towards abstraction, the influence of Lautrec's expressive distortion and flair for exaggeration remained a persistent undercurrent in Picasso's work. This can be seen in Picasso’s later, more experimental periods, such as Cubism, where forms are broken and reassembled in exaggerated, often fragmented ways. In many ways, Lautrec’s legacy in Picasso’s oeuvre is a testament to their shared commitment to portraying the vibrancy, complexity, and often harsh realities of contemporary life, but through uniquely personal and transformative visual languages.

African Art: A Turning Point for Picasso

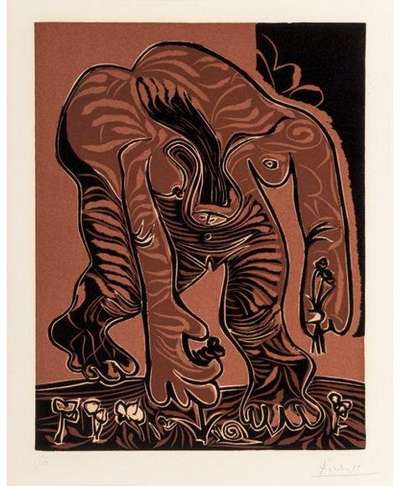

Picasso’s encounter with African art in 1907 marked a decisive turning point in his artistic journey, deeply influencing his development of Cubism. The bold geometric abstraction of African masks and sculptures challenged Picasso to rethink the representation of the human figure, and offered a new visual language for breaking down and reconstructing reality. Yet this influence of African art reveals a more complicated dialogue that cannot be reduced to simple terms of inspiration.

In the early twentieth-century, African art was often viewed by European artists and collectors through the lens of primitivism, a concept rooted in colonial ideologies. This ideology reflected a Eurocentric mindset that regarded non-Western cultures as less developed or sophisticated, imposing a hierarchical view that diminished the complexity and cultural significance of these objects. Rather than recognising African art as part of rich, diverse artistic traditions with their own histories and spiritual meanings, Western artists often appropriated these works solely for their aesthetic qualities, disconnected from their original contexts. Picasso’s interest in African masks and sculptures was largely formal, and focused on their visual power, but this detached them from the communities that created them. In Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the mask-like faces reveal Picasso’s embrace of this art style, but they also illustrate a broader issue; the selective appropriation of African art by European modernists. Picasso, like many of his contemporaries, saw African art as a means to break free from the constraints of classical Western traditions, but in doing so, he participated in a form of cultural extraction, taking visual ideas without engaging with their broader significance.

The problematic nature of this engagement becomes clear when considering the colonial dynamics at play. African art was frequently exhibited in ethnographic museums, categorised alongside artefacts from colonised territories, reinforcing the notion that these objects were artefacts of “otherness” rather than fully realised works of art. Picasso’s use of African forms, however revolutionary it may have been in the context of Cubism, must be understood against this backdrop of colonialism, where non-Western cultures were often marginalised and decontextualised to serve Western artistic ambitions.

Picasso’s legacy in this regard is complex. On one hand, Picasso’s relationship with African art is emblematic of the tensions between modernist experimentation and the colonial contexts in which these exchanges occurred. While his work represents a major artistic breakthrough, it also invites reflection on how Western art history has often been built on the borrowing, and sometimes the distortion, of non-Western cultural forms. Picasso’s genius lay in his ability to synthesise multiple influences into something radically new, but his legacy also prompts us to question the ethical implications of such cross-cultural encounters and the power dynamics that shaped them.

Georges Braque: A Collaborator and Co-Founder of Cubism

Georges Braque was not simply a counterpart to Picasso, but an integral partner in the radical transformation of modern art through their pioneering work on Cubism. Beginning in 1909, the collaboration between Braque and Picasso was symbiotic, marked by an intense creative dialogue that blurred the boundaries of individual authorship. Far from being a mere influence, Braque played a critical role in shaping key elements of both Analytic and Synthetic Cubism, contributing techniques and ideas that would redefine the very language of painting. What distinguished their partnership was the deep intellectual exchange and mutual respect. In their work, they explored the concept of simultaneity, depicting multiple perspectives within a single composition, thereby dismantling the traditional one-point perspective that had governed Western art for centuries. This conceptual shift was not a solo endeavour, but a shared revolution. Braque’s more methodical approach complemented Picasso’s intuitive, experimental nature, creating a dynamic push and pull that pushed Cubism into new, unexplored territories.

Although Picasso has often been positioned as the more celebrated figure, Braque's contributions were equally significant, particularly in the early stages of Cubism’s evolution. Their work during this period was so closely intertwined that even today, many of their paintings from 1910 to 1912 are nearly indistinguishable in style. Together, they not only redefined the visual representation of reality, but also opened up new questions about the nature of perception, representation, and the role of the artist.

Henri Matisse: A Rivalry That Shaped Modern Art

The relationship between Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse was characterised by a complex interplay of rivalry and mutual inspiration that profoundly influenced the trajectory of modern art. While often described as adversaries, their competitive spirit functioned more as a creative dialogue, compelling both artists to continuously push the boundaries of their work. This dynamic was rooted in their contrasting yet complementary approaches to art; Matisse’s bold, expressive use of colour and form stood in stark contrast to Picasso’s earlier, more monochromatic palettes, yet each artist learned from the other, leading to a rich cross-pollination of ideas.

Matisse’s exploration of colour and use of flat planes challenged Picasso to reconsider his own artistic conventions. As he ventured into the realms of sculpture and ceramics, Picasso embraced a more vibrant colour palette, incorporating the vivacity of Matisse’s style into his own. This transformation reflects a broader trend within Picasso’s evolution as an artist, showcasing his ability to synthesise various influences while still maintaining his unique voice.

Edgar Degas: Master of Movement

Picasso’s relationship with the work of Edgar Degas offers a compelling example of how one artist’s influence can permeate another’s career without direct interaction. Although they lived in close proximity in Montmartre for several years, there is no evidence they ever met. Yet, Degas’ impact on Picasso is evident in key aspects of his work. Early in his career, Picasso's depictions of Parisian life, cafés, cabarets, and bathers, clearly echo Degas’ favoured subjects, but these themes were reimagined through Picasso’s distinct stylistic lens. The influence deepened when Picasso married Olga Khokhlova, a dancer, leading to a series of works that drew directly from Degas' established vocabulary of ballerinas and their world.

Degas’ realism and his attention to intimate, often unglamorous moments found a parallel in Picasso’s evolving style, particularly in his explorations of the body and human vulnerability. The purchase of Degas’ brothel monotypes in 1958 reinforced this connection, with Picasso later incorporating Degas himself into his etchings of similar scenes. Both artists were grounded in rigorous academic training, yet each subverted tradition to delve into more psychologically and socially charged subjects. Picasso’s sustained engagement with Degas’ work reflects not only admiration but also a nuanced, evolving dialogue with the themes and techniques that had preoccupied Degas throughout his career.

In tracing the arc of Picasso's artistic evolution, it is evident that his revolutionary style was not forged in isolation but through a dynamic and complex engagement with a wide range of influences. On the one hand, Picasso’s genius lay in his ability to constantly absorb, reimagine, and reinterpret the ideas of those who came before him. On the other, Picasso’s use of African stylism, while transformative for modernist aesthetics, raises important questions about the power dynamics that underpinned such cultural encounters. Picasso’s legacy is a complex one, intertwined with both innovation and appropriation, revealing the deep interconnectedness of global artistic traditions. Picasso’s work stands as a testament to the transformative power of influence and the ongoing dialogue between art, culture, and history.