Artists Who Inspired Helen Frankenthaler

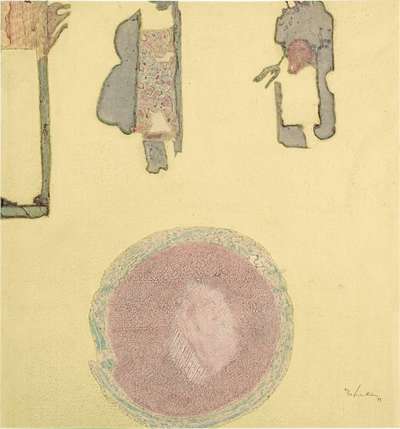

The Red Sea © Helen Frankenthaler 1982

The Red Sea © Helen Frankenthaler 1982

Helena Poole, Specialisthelena.poole@myartbroker.com

Interested in buying or selling

Helen Frankenthaler?

Helen Frankenthaler

80 works

Key Takeaways

Helen Frankenthaler drew inspiration from a range of influential artists who helped shape her distinctive style. Known for her innovative soak-stain technique, Frankenthaler transformed the way paint interacted with canvas, creating expansive fields of color. Her work was influenced by a number of artistic giants, including Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, who helped her carve a unique path in the post-war Abstract Expressionist era, leaving a lasting impact on modern art.

Helen Frankenthaler was a pioneer of the Color Field movement and a key player in the post-war Abstract Expressionist era. Her signature soak-stain technique was inspired by the radical approaches of those who came before her. Artists including Jackson Pollock, Paul Cézanne, and Hans Hofmann introduced her to new possibilities involving paint, colour, and the canvas itself. By thinning her paints and pouring them onto raw, unprimed canvas, Frankenthaler created uniquely luminous, flowing fields of colour that merged with the fabric of the canvas, transforming modern art in the process. This groundbreaking approach distinguished her from her peers, and her work became central to the development of Color Field painting.

Jackson Pollock: Pioneering Abstract Expressionism

Jackson Pollock, a seminal figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement, exerted a profound and lasting influence on Frankenthaler, shaping her approach to abstraction in ways that would define her career. Pollock’s revolutionary drip painting technique marked a radical departure from traditional methods of applying paint to canvas, transforming the nature of artistic expression in the postwar era. By dripping enamel directly onto the canvas laid flat on the floor, Pollock challenged the conventions of composition, form, and depth. His process, deeply physical and unmediated by traditional tools, fostered an immersive engagement with the material itself. Pollock's innovative treatment of the canvas as a raw, expansive surface, devoid of preconceived structure, opened new possibilities for subsequent generations of artists. His rejection of the easel and his dynamic techniques emphasised the process of creation as a form of spontaneous gesture, rather than a deliberate construction. Frankenthaler was particularly inspired by this liberation from formal constraints, finding in Pollock's methods a model for her own artistic experimentation.

This influence is most evident in Frankenthaler's development of the ‘soak-stain’ technique, a pivotal innovation culminating in her 1952 work Mountains and Sea. While Pollock’s enamel paints remained on the canvas's surface, Frankenthaler sought a deeper integration of paint and canvas, using oil paints thinned with turpentine. This allowed the pigment to seep into the unprimed canvas, creating an effect that was simultaneously fluid and organic, as if the colours had naturally soaked into the fabric rather than been applied onto it. The soft, transparent washes of colour that emerged in her work introduced a sense of immediacy and intimacy, as though the painting was imbued with its own natural movement.

Frankenthaler’s technique was more than just a formal innovation; it represented a conceptual shift that aligned with Pollock's emphasis on the act of painting as an event in itself. Like Pollock, Frankenthaler embraced the physicality of the creative process, with each gesture becoming a vital part of the artwork’s identity. Her method broke with traditional brushwork, favouring an intuitive, almost performative approach that prioritised the painter’s relationship with the canvas. By doing so, Frankenthaler not only expanded the vocabulary of abstraction, but also carved out a distinctive space within the broader trajectory of postwar American art, where the materiality of paint and the directness of the artist’s interaction with the medium became central concerns. In this way, Pollock’s influence on Frankenthaler inspired her to reconsider the very nature of painting itself. His pioneering approach fueled her own exploration into the depths of abstraction, leaving an indelible mark on the evolution of modern art.

Paul Cézanne: Master of Composition and Structure

Though separated by time and artistic movements, the influence of Paul Cézanne on Frankenthaler’s work is both significant and nuanced. Cézanne, a pioneering Post-Impressionist, profoundly shaped modern art with his innovative approach to depicting depth, form, and spatial relationships through subtle shifts in colour and brushstroke. His meticulous exploration of space, and his treatment of the canvas as an arena for balancing structure and colour, found deep resonance with Frankenthaler, particularly as she developed her own strategies for composing large, abstract canvases.

Cézanne's mastery lay in his ability to redefine the representation of space and volume through colour modulation rather than traditional linear perspective. For Frankenthaler, this aspect of his work provided a foundational understanding of how to approach the challenges of filling expansive surfaces. Cézanne’s use of gradations of tone and hue to suggest depth and form was especially instructive to Frankenthaler, who was concerned with balancing large areas of colour to create both harmony and tension within the composition. His work influenced her to think of colour as an active force in shaping the structure of her paintings.

One of Cézanne’s most revolutionary techniques, leaving portions of the canvas exposed, paralleled Frankenthaler’s own approach to abstraction. In works such as Gardanne (1885-86), Cézanne left raw patches of canvas, emphasising the interplay between what was painted and what was left bare. This strategic use of emptiness within the composition deeply influenced Frankenthaler’s aesthetic. In her soak-stain technique, Frankenthaler also embraced the idea of the canvas as an integral element of the work, with the raw, unprimed surface playing an active role in the final composition. By allowing the paint to seep into the fibres of the canvas, she created luminous, transparent fields of colour that echoed Cézanne’s ability to imbue a surface with depth and atmosphere through restraint.

Thus, while Cézanne and Frankenthaler operated in different historical and stylistic contexts, his approach to colour, composition, and the treatment of space played a pivotal role in shaping her unique voice within the larger trajectory of modern art. His legacy can be seen in the sophistication with which Frankenthaler handled the expansive surfaces of her canvases, using colour to evoke complex atmospheres while maintaining a sense of balance, depth, and structural integrity.

Hans Hofmann: Frankenthaler’s Mentor and Colour Theorist

Hans Hofmann, a renowned figure in abstract painting, and one of the most impactful teachers of 20th-century modern art, played a critical role in shaping Frankenthaler’s artistic development, particularly in her understanding of colour and form. As one of Frankenthaler’s early mentors, Hofmann provided her with a rigorous theoretical foundation that would profoundly influence her exploration of abstraction. His guidance introduced her to the idea of colour as a powerful, independent force within a composition, capable of generating both emotion and structure without the need for traditional representation.

Hofmann’s concept of the ‘push-pull’ effect was particularly transformative for Frankenthaler. This theory described how colours could be used dynamically to create a sense of movement and spatial depth on the canvas. By juxtaposing warm and cool tones, or light and dark hues, artists could make areas of the painting seem to advance or recede, giving the flat surface of the canvas an almost three-dimensional quality. Frankenthaler integrated this into her own work, where she developed a distinct method of creating depth not through linear perspective or representational forms, but through the interaction of expansive fields of colour. Hofmann’s insistence on the power of colour to evoke space and movement liberated her from more traditional approaches to composition, enabling her to engage with colour in an intuitive and fluid manner.

Hofmann’s influence also played a crucial role in Frankenthaler’s emergence as a leading figure in the Color Field movement. His ideas about the flatness of the canvas and the autonomy of colour laid the groundwork for the movement’s emphasis on large, unmodulated fields of colour that seemed to float across the surface. Frankenthaler took these principles and expanded upon them, her work moving beyond Hofmann’s gestural abstraction to find a more meditative, contemplative expression of colour. By absorbing and then transcending Hofmann’s lessons, Frankenthaler was able to carve out a distinctive place for herself in the broader history of modern art, where her contributions to Color Field painting continue to be celebrated for their innovation and emotional resonance.

Clement Greenberg: The Art Critic Who Shaped Her Path

Clement Greenberg, an influential and discerning art critic of the 20th century, played a pivotal role in establishing Frankenthaler as a central figure in postwar American art. His early recognition of Frankenthaler’s innovation, notably her soak-stain technique, underscored his belief that her work represented a significant evolution in the trajectory of abstract painting. Greenberg saw in Frankenthaler a bridge between the gestural dynamism of Abstract Expressionism, and the emerging trends in Color Field painting, which he championed as the next phase of abstraction. He believed that Frankenthaler's soak-stain method marked a fundamental shift in the treatment of colour, space, and surface. By removing the physicality of the brushstroke, Frankenthaler’s technique allowed for a more fluid, immersive relationship between paint and canvas, a development that Greenberg saw as emblematic of modernism's move toward purity and the prioritisation of formal properties.

Greenberg’s support, particularly in the early stages of Frankenthaler’s development, helped to elevate her profile within the competitive New York art scene. Greenberg facilitated her introduction to leading figures of the time, such as Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and other influential Abstract Expressionists, which expanded her exposure to critical conversations and practices that would shape her work. His close relationship with these artists and his role as an arbiter of avant-garde movements positioned Frankenthaler at the heart of contemporary artistic discourse. One of the most significant moments in Frankenthaler’s career came with her inclusion in Greenberg’s landmark 1964 exhibition, Post-Painterly Abstraction. This exhibition, which introduced a new generation of artists moving beyond the gestural brushwork of Abstract Expressionism, was instrumental in defining Color Field painting as a dominant force in the 1960s. Greenberg’s curation of this show placed Frankenthaler alongside artists such as Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, cementing her reputation as a key innovator in the movement.

Mark Rothko: Emotional Depth and Colour as a Language

Mark Rothko’s monumental canvases, dominated by luminous, floating fields of colour, exerted a profound and lasting influence on Frankenthaler’s own approach to colour as a vehicle for emotional expression. Rothko’s ability to use colour to communicate deep emotional resonance was revolutionary. His works, often large enough to envelop the viewer, created immersive environments that invited a meditative experience. Rothko’s influence on Frankenthaler centred around this shared belief in the evocative potential of colour. While Rothko tended toward darker, more intense hues to convey feelings of weight and depth, Frankenthaler translated this emotional power into a lighter, more fluid vocabulary.

Despite these differences, Rothko’s influence is evident in Frankenthaler’s ability to create emotive, expansive fields of colour that engage the viewer on a visceral level. Like Rothko, she believed in the inherent power of colour to evoke an emotional response, unmediated by form or subject matter. Frankenthaler, however, brought her own sensibility to this idea, often choosing colours that were lighter and more spontaneous. Both artists, through their distinct but related practices, elevated colour to a language that transcends form and narrative, speaking directly to the viewer's emotional and sensory experience.

Arshile Gorky: A Bridge Between Surrealism and Abstraction

Arshile Gorky, a figure who bridged surrealism and abstraction, significantly inspired Frankenthaler’s early exploration of organic forms and fluid shapes. Gorky’s unique ability to merge the dreamlike, psychological underpinnings of surrealism with the formal innovations of abstraction provided Frankenthaler with a critical model for how abstraction could convey personal emotion without relying on representational imagery. Compositions such as Image In Khorkom (1936), filled with biomorphic forms and flowing lines, inspired Frankenthaler to delve into non-representational painting while maintaining a strong emotional connection to her work.

Gorky’s influence on Frankenthaler extended beyond form to a deeper understanding of the interplay between spontaneity and personal expression in art. His synthesis of abstraction with emotional depth resonated with Frankenthaler, whose early works often featured similar biomorphic shapes and an embrace of fluidity. Like Gorky, Frankenthaler sought to create compositions that felt organic, as though they were naturally emerging from the canvas, rather than constructed according to rigid formal guidelines.

In this context, Frankenthaler’s development as an artist can be seen as the product of a rich and diverse range of influences, each contributing to her unique approach to form, colour, and emotion. While Pollock’s radical abstraction encouraged her to abandon traditional brushwork, Gorky’s influence provided her with a model for integrating fluid forms with personal emotional content. Cézanne’s compositional mastery encouraged Frankenthaler to think critically about structure and spatial relationships, while Rothko’s emotional depth demonstrated the potential of colour as a direct conduit for human feeling. Each of these artists inspired Frankenthaler’s distinctive voice within the Abstract Expressionist and Color Field movements, where her work stood out for its balance of formal innovation and deeply personal expression.